Mental health professionals working in youth services often witness a troubling pattern: the very systems designed to help young people sometimes push them away. Today we explore how evidence-based interventions and trauma-informed practices can paradoxically transform struggling youth into adversaries of their own support systems.

The Intervention Paradox

Across mental health centers, a consistent scenario emerges. Imagine Maria—seventeen years old, navigating legitimate struggles with anxiety and family conflict. She enters a system staffed by caring professionals armed with proven methodologies. Yet months later, she delivers a verdict that echoes through countless programs:

“You people don’t get it. You come in here with your programs and your worksheets, acting like you’re saving us. But all you’re doing is making things worse.”

This pattern reveals a fundamental paradox in youth mental health services. Military strategist David Kilcullen identified something called the “accidental guerrilla syndrome”—how interventions targeting small problems often create larger resistance movements. The parallel to youth work proves both startling and illuminating.

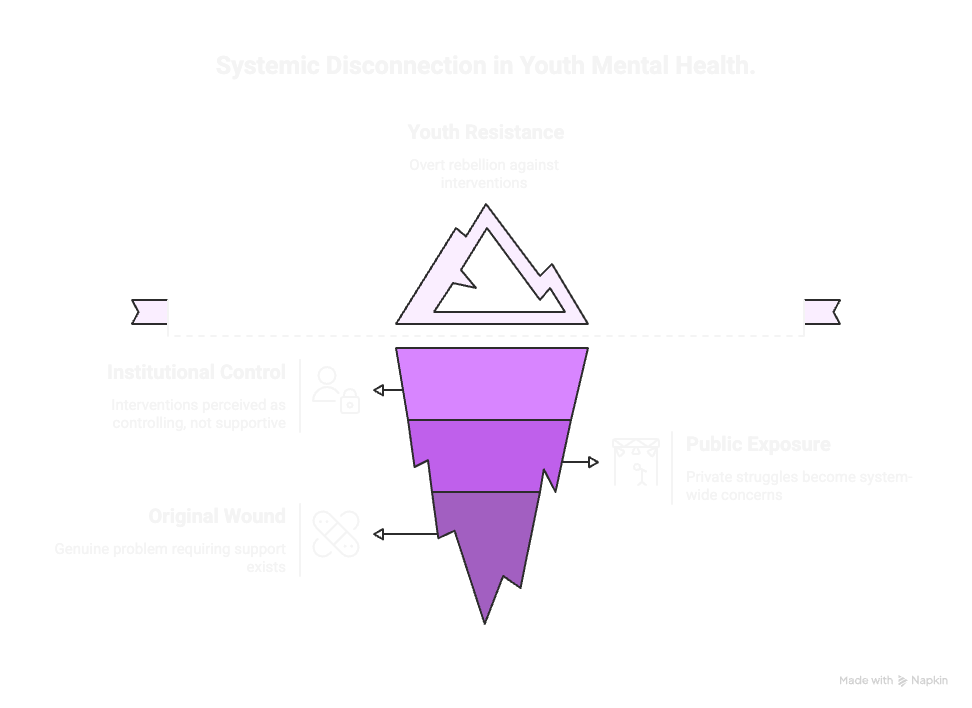

The Four Stages of Systemic Disconnection

Examining typical youth journeys through mental health systems reveals a predictable pattern of how help transforms into harm:

1. Infection: The Original Wound

A genuine problem exists requiring support. The young person faces real struggles—anxiety, family conflict, trauma responses. The pain is authentic, the need for support legitimate. Yet systems often see only the problem, not the person carrying it.

2. Contagion: The Spread of Visibility

The scenario is common: We imagine Maria’s school attendance drops—a metric that triggers concern. Teachers notice, referrals are made, systems activate. Her private struggle becomes public property. What begins as individual difficulty spreads through institutional awareness, transforming personal challenges into system-wide concerns.

3. Intervention: The Descent of Help

Here, good intentions pave roads to resistance. Systems deploy their full arsenal:

- Mandatory counseling sessions that feel like surveillance

- Behavior contracts that reduce youth to compliance metrics

- Parent meetings that expose family dynamics

- Psychiatric evaluations that catalogue dysfunction

Each intervention follows evidence-based protocols, delivered by trained professionals. Yet youth experience these as layers of institutional control rather than genuine support.

4. Rejection: The Creation of the Adversary

Young people don’t experience these interventions as help. They experience invasion—another source of stress, another system attempting control, another group of adults who fail to understand. They begin resisting actively: skipping appointments, recruiting peers to validate their rebellion. The system has created the very adversary it sought to help.

The Humbling Truth

This framework forces uncomfortable realizations about standard practice. The intensity and visibility of interventions often make professionals part of the problem. The field confuses activity with effectiveness, programs with relationships, professional expertise with genuine understanding.

Research confirms this pattern. Young people consistently report feeling “over-serviced and under-connected.” They experience help as something done to them rather than with them. Professional presence becomes a marker of their difference, their problems, their failure to achieve “normal” teenage life.

Finding Alternative Pathways

Recognizing these patterns opens doors to transformation. The same framework diagnosing the problem points toward solutions—not through abandoning the desire to help, but through reimagining what help looks like.

It is young people who teach us this lesson. Instead of surrounding them with services, effective programs begin with different questions: “What’s working well in your life right now?” Rather than focusing on diagnosed anxiety disorders, they notice gifts—perhaps music, art, or leadership. Instead of mandating counseling, they connect youth with mentors who understand both their talents and their struggles.

Walking away from such interactions, a young person says to herself:

“You know what’s different? They didn’t try to fix me. They just saw me.”

The Strategic Shift

This approach requires fundamental reorientation—moving from deficit-focused to strength-based operations. In practical terms, this means:

From Deficit-Focused to Asset-Based

- Traditional approach: Define youth by diagnoses and dysfunctions

- Alternative approach: Recognize strengths used to navigate difficulties

- The shift: Stop asking “What’s wrong?” Start asking “What’s strong?”

From Intervention to Integration

- Traditional approach: Create separate, clinical spaces for help

- Alternative approach: Embed support within existing youth ecosystems

- The shift: Meet youth where they are, not where professionals feel comfortable

From Visible to Invisible

- Traditional approach: Make helping highly visible and documented

- Alternative approach: Sometimes the best help doesn’t look like help

- The shift: Support that feels like friendship, not treatment

From Professional Distance to Authentic Relationship

- Traditional approach: Maintain clear boundaries and clinical objectivity

- Alternative approach: Risk the vulnerability of genuine human connection

- The shift: Real healing happens between real people

Critical Questions for System Evaluation

Mental health boards and executive directors hold power to reshape how organizations engage with youth. These diagnostic questions serve as invitations to honest system assessment:

-

The Question of Origin: What percentage of youth programs emerged from youth requests versus adult assumptions about their needs?

-

The Question of Choice: How many young people experience services as voluntary sanctuaries versus mandatory sentences?

-

The Question of Resistance: When youth resist programs, does the system interpret this as a problem to overcome or as feedback to integrate?

-

The Question of Measurement: Does the organization measure success by services provided or by how connected youth feel?

-

The Question of Identity: Do youth see the organization as a place they must go or a place they choose to be?

Transformative Possibilities

Programs that recognize these patterns often see remarkable transformations. Young people like our imagined Maria return—but on fundamentally different terms. They become peer mentors, helping redesign intake processes from the ground up. Their insights prove revolutionary in their simplicity: the question isn’t “How can we help you?” but “What are you already doing to help yourself, and how can we support that?”

The “accidental adversary” framework teaches that sometimes the most powerful intervention is to intervene less. Sometimes the most helpful action is to stop trying so hard to help and start trying harder to understand.

The Continuous Practice

This recognition—that best intentions aren’t enough—represents not a destination but a beginning. Each day offers opportunities to choose differently. When professionals feel the impulse to assess before connecting, diagnose before understanding, intervene before listening, they can pause and consider:

- What remains unseen in this situation?

- Whose story is being overwritten with professional narratives?

- How might professional presence be experienced by someone who has learned that systems of care carry hidden costs?

The pattern, once recognized, can be changed. That change begins with a simple but radical shift: seeing youth not as problems requiring solutions, but as full human beings already engaged in the complex work of navigating their lives.

Moving Forward

Mental health systems stand at a crossroads. They can continue operating as accidental adversaries, creating resistance through attempts to help. Or they can develop the humility to learn different ways of being present—approaches that honor the full humanity of those they serve.

The challenge facing youth mental health services isn’t about acquiring better interventions or more evidence-based practices. It’s about fundamental transformation in how professionals understand their role: shifting from experts who fix to partners who accompany, from systems that control to communities that support.

The invitation before mental health professionals is clear: examine not just methods but fundamental stances toward those encountered in this work. In that examination lies the possibility of transformation—not just for the youth served, but for professionals and the systems they inhabit. Sometimes the most revolutionary act is simply to stop, to listen, to allow ourselves to be taught by those we thought we were teaching.